A microbial organism pulls electricity from water in the air.

The mad rush is on for discovering clean and renewable forms of energy before it’s too late. Turns out, researchers may have unknowingly had it in hand for decades. It’s a sediment organism first found along the muddy shores of the Potomac River and reported in a letter to the journal Nature in 1987. It turns out the microbe produces electricity out of thin air, one resource we’re unlikely to run out of. University of Massachusetts Amherst scientists have just revealed their development of a device for harvesting this electricity in Nature.

Image source: Anna Klimes and Ernie Carbone, UMass Amherst/Wikipedia

THE AMAZING MICROBE

The rod-shaped microbe, Geobacter sulfurreducens is, as its name implies, a member of the Geobacter genus, a group referred to as “electrigens” for their known ability to generate an electrical charge. It was UMass Amherst microbiologist Derek Lovley who found and wrote about the microbe in the late 80s.

It was also Lovlley’s lab that discovered the microbe has a talent for producing electrically conductive protein nanowires, and his lab recently developed a new Geobacter strain that could produce them more rapidly and inexpensively. “We turned E. coli into a protein nanowire factory,” Lovley says. What this means, he says, is that “With this new scalable process, protein nanowire supply will no longer be a bottleneck to developing these applications.”

Enter electrical engineer Jun Yao, also of UMass Amherst. His specialty had been engineering electronic devices using silicon nanowires. The two decided to work together to see if they could turn Geobacter’s protein nanowires into something useful.

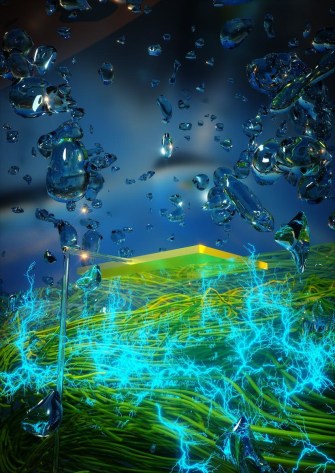

Artisit’s conception of the duo’s Air-gen, with Geobacter’s charge-producing nanowires imagined beneath the device.

Image source: UMass Amherst/Yao and Lovley labs

AIR-GEN

The fruit of their collaboration is a device they call “Air-gen.” It employs a thin film of Geobacter nanowires less than 10 microns thick resting on an electrode. Another, smaller electrode sits on top of the film. The film collects, or adsorbs, water vapor, and its surface chemistry and conductivity produce a charge that passes between the two electrodes through the fine gaps between individual nanowires.

Yao’s doctoral student Xiaomeng Liu recalls, “I saw that when the nanowires were contacted with electrodes in a specific way the devices generated a current. I found that that exposure to atmospheric humidity was essential and that protein nanowires adsorbed water, producing a voltage gradient across the device.”

Says Yao, “We are literally making electricity out of thin air.” The Air-gen generates clean energy 24/7. “It’s the most amazing and exciting application of protein nanowires yet.” The two see their new technology as being non-polluting, renewable, and low cost- with distinct advantages over other developing energy sources such as solar and wind for at least one big reason, “it even works indoors” notes Lovley.

Air-gen producing electrical current

Image source: UMass Amherst/Yao and Lovley labs

SOMETHING IN THE AIR

At this point, Air-gen generates “a sustained voltage of around 0.5 volts across a 7-micrometre-thick film, with a current density of around 17 microamperes per square centimeter,” enough power to run small electronics. Chaining together several Air-gen units produces even more voltage. The device marks an obvious advance beyond other existing moisture-based energy-harvesting devices that are capable only of intermittent bursts of electricity that last less than 50 seconds.

Lovley and Yao plan Air-gen modifications that will allow Air-gen to replace the batteries used in electronic wearables — smart watches and other health and fitness devices — providing self-renewing energy. They also expect it to soon provide power for mobile phones the user will no longer need to recharge.https://3f19543281114dfebcd73a11076e6427.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.html

“The ultimate goal,” says Yao, “is to make large-scale systems. For example, the technology might be incorporated into wall paint that could help power your home. Or, we may develop stand-alone air-powered generators that supply electricity off the grid. Once we get to an industrial scale for wire production, I fully expect that we can make large systems that will make a major contribution to sustainable energy production.”

Clearly excited by the work so far, Yao says, “This is just the beginning of new era of protein-based electronic devices.”